Artist Dialogues

Indira Allegra

Lola Arias

Lise Halle Baggesen

Iris Bernblum

Mary Helena Clark

Hope Esser

Max Guy

Meredith Haggerty

Cameron Harvey

Jaclyn Jacunski

Anna Elise Johnson

Asa Mendelsohn

Jenny Polak & Díaz Lewis

Cheryl Pope

Michele Pred

Sarah Ross

Alison Ruttan

Deb Sokolow

Deborah Stratman

Marilyn Volkman

Krista Wortendyke

In conversation with Indira Allegra

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

Your work in Take Care, Did My Tumor Exhale A Memory of You? (2017), is a 4-channel immersive sound installation that, at once, makes us feel as though we are inside the safety of the womb, while knowing we are in fact posited to be inside a malignant tumor. How did you arrive at the idea of placing the viewer inside the body, perhaps even inside a representation of your own body?

Indira Allegra

I truly believe anything with blood flow has memory and memory is a space that can be entered. We know tumors can be entered by blood or the steel edge of a scalpel so the question was never, “Can a tumor be entered?” but “On what scale must the tumor exist for the entirety of one’s body to enter that organ of memory?” Did My Tumor Exhale A Memory of You, makes this organ of memory large enough for our bodies to slip through its membrane. I’ve had two tumors removed from my body in two years — in each case I had to wonder what knowing these masses were holding for me. After this last surgery, I began to wonder how the memory in my tumor might actually be dispersed once it was incinerated — how something so unwittingly intimate could now be dispersed as smoke through the act of incineration and inhaled by other people. It startled me to think that perhaps I had been inhaling the memories of other peoples’ tumors my whole life.

WNG

In your artist statement you talk about using tension as creative material, which we can certainly feel in this installation. It possesses a simultaneous sensation of comfort and terror, in large part due to the sound. The singing channel is particularly haunting and I can’t help but draw a parallel to the myth of the “siren song” — a deceptive seduction. Everything in the installation contributes to this feeling — from the warmth of the space to the vibrancy of color emanating from the corner of the room as one’s eyes slowly adjust to the darkness. All the elements draw us in towards the soft, lulling sound of your voice, but like the Siren draws a sailor to their death, you draw us into the cancer. Can you tell us more about your relationship to tension? And more specifically, about settling in and living/working in that space of tension?

IA

Ah wow. Yes. Well I relate to tension as a material as it is something I can feel with my body and also feel outside of my body in space or between people. Like other materials, tension seems to vary in density and quantity — with multiple tensions able to act on a person or place at once. Like other materials, tension can be created, carried, shaped or released. It is the stuff in our backgrounds that pulls on our personalities, and bends our bodies toward illness or injury. It is the stuff in our collective histories that ‘stretches us thin’ causing us to cycle through fight, flight or freeze responses in relation to politicians or policies. From the resistance of our bones to gravity to the resistance of social movements to the powers that be — tension is the medium all of us are made of. It exists in abundance.

When I arrived at the hospital last year for my first surgery, I felt a dense — heavy twist in my stomach when the man at the counter could not — for a moment — determine if my insurance was actually in-network. So suddenly, a primary tension was created between my need for care and the hospital’s desire to guarantee payment in a society where people who cannot pay often do not receive the treatment they need. A secondary tension arose for me surrounding my fear of being abandoned emotionally by white members of my care team due to longstanding histories of racism and racist abuse of Black and Native women by the medical industrial complex. Then a third tension developed — would the presence of my genderqueer partner be respected as my family member in this setting? The receptionist was looking us both over, asking again if my partner should be considered family to me…

In each of these cases, the experience of being pulled between forces — between my needs and boundaries and the hospital’s needs and boundaries — had a real impact on my body. These were tensions felt also by my partner standing next to me at the counter. The tension in the room was undeniable and palpable. For me, as a queer woman of color and as a low-income person, this palpability of tension is something I encounter multiple times a day on a daily basis. So much so, I have a fluency in the feeling of it. A hyper-literacy associated with the reading of social silence. And then what? How to work with a material that is both exhausting and inexhaustible in its supply? My training as a weaver affords me the patience to investigate pattern and structure (over and over again), my work as a poet allows me to craft connections between disparate bodies. My past experience as a sign language interpreter engenders an impulse in me to create texts through the movement of the body.

WNG

Let’s discuss the title of this piece, Did my tumor exhale a memory of you? You also did a performance piece earlier this year titled, What do tumors know that we forget when they are cut from the body? — this line is embedded within the text of your sound installation, as well. Can you explain to us your perspective on tumors having memory?

IA

In my case, each of my tumors was a convergence of different kinds of tissues overpopulating a small area. But what pain from this overpopulation. I am lucky my tumors were benign medically, but energetically, there was nothing benign about them. Growing in the crease of my hip and another surrounding my ovary, each crowding of cells was an overpopulation of ungrieved events triggered by environmental toxins and genetic predispositions. I feel my body created a room for every ungrieved thing in these tissues. That is the double-edged, nature of the cell — it confines energies, people and objects even as it is able to multiply. Everyone has a (necessarily) different understanding of their tumor(s) but for me — my understanding is that my tumors were holding ungrieved memories that were too heavy for me to consciously articulate as a written or spoken text. So my body created another kind of text — ones that grew quietly until they could no longer be ignored.

WNG

You worked closely with Take Care curator, Kasia Houlihan, on the physical execution of this piece — communicating ideas and sharing sketches over many months together. As an artist, how would you describe that process of having an extensive project idea and trusting someone else with the care of seeing it through?

IA

Working with Kasia was a dream. Without ever having met each other, I felt we each extended a kind of trust to each other via email. She communicated her respect and professionalism to me outright by asking how much I would need to make the work. Her flexibility with my residency schedule at the Headlands Center for the Arts this summer, was another significant offering. Also, Kasia did not ask for every detail of the work to be described to her in one go, and that was a great relief — to be able to reveal to her the shape of the work as it became clear to me. Because that’s how artists work — we discover things as we go along. Her questions were often helpful prompts for me to sit down and think — hmmm, what material should the floor be made of?.

When I stated a need around temperature, color, material, sound etc. Kasia sprung into action to see how we could make it happen or who she could talk to on her end to get advice about it. I loved that. I appreciated that so much. When, as an artist, a curator expresses equal investment (and encouragement) in the development of a work — it really, really helps. It was Kasia’s ‘let’s-do-this-and-communicate-in-detail’ attitude about making things happen and sharing information that made it a joy to trust her. I don’t know any artists who make work because it is easy or because they think art should be beautiful — I know folks who make work because it is best way they know how to articulate really difficult or really critical questions about or responses to aspects of the lived experience. That means making work can sometimes be very stressful. When you feel that a curator is on your team, it makes you feel that you can really focus on wrestling with the tension in the work instead of the tension in your body around upcoming deadlines.

WNG

You’re about to take off for a month long residency at Djerassi, what do you plan to work on while you’re there?

IA

Oh, I’m doing more work on the Bodywarp series in an old abandoned barn. It is a series wherein I get to switch roles and go from being the weaver to being the thread and put the tension in my body on the loom as creative material. I get to submit to the loom in a way, to trust the loom with the weight of me not just the weight of my expectations for the cloth being produced. You can see some of the work at my solo show opening January 6th, 2018 at The Alice Gallery in Seattle. Otherwise, I’m just catching up on the million little things that go into the business of being an artist — editing this, uploading that, updating this, re-writing that. At Djerassi, they talk a lot about giving artists “the gift of time” to “just be” and it is truly such a relief to be honest. I wish we did not have to contend with a society that is so completely bullied by the (perceived) scarcity of time. People forget that artists go through periods of rest, research, incubation and reorganization of our archives like everyone else. Sometimes days in studio include afternoons and evenings at the computer crafting paragraphs for grants and applications, statements and interviews. In this case, it was my pleasure to “just be” with your questions.

In conversation with Lola Arias

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

Can you give a short overview of your practice, specifically how you became interested in the theatrical?

Lola Arias

I studied literature and theater, and I started to write poetry, fiction, and plays. Then I began directing my own plays. I was interested in the interdisciplinary aspect of theater, which is in itself a mixture of literature, visual arts, music and acting.

My first plays were more conventional so to say (a fictional story performed by actors) and then I started to be more interested in exploring the boundaries between documentary and fiction. I did a play called My life after with a group of people who were born during the military dictatorship in Argentina, whose parents were part of the guerrilla or policemen or exiled intellectuals. And from then on, I did several projects based on previous research and performed by all kinds of people: Bulgarian immigrate kids, street musicians, beggars, prostitutes, policemen, veterans of a War. These projects are theater plays but also urban interventions, installations and video installations.

WNG

A lot of your work juxtaposes the intensity of a historical event with the levity of retelling or re-enacting this event. In the re-enactments you reveal the mise en scène of stage production, elements that would typically be off camera, i.e. booms, light stands, markers, fans etc. What was your impetus for giving the viewer access to the surrounding scene?

LA

I see the re-enactment as a way to travel in time, to bring the past into our present. Whenever we talked about history we think it’s something that happened in the past to someone else, but the past is inside every one of us every single moment of our lives. In the case of war veterans, this can be traumatic because they are reliving their war experiences in their daily lives. Sometimes a flashback of the war interrupts their routine, bringing back the image of a dead body or the sound of a bomb or a missing friend.

When I re-enact the past with people, I try to show how difficult it is to bring back something that is gone. So, instead of pretending that we know how it was, like a realistic representation would do, I prefer to show how we try to stage it. When you see the elements of the mise en scène, you also see that it’s an attempt to recover the experience.

WNG

Your performers regularly break the fourth wall, and while doing so they seem to take on a rather dry, emotionally removed rendition of their story. What drew you to using this theatrical trope and what emotional response do you hope to evoke from viewers as they experience your work?

LA

When the performers are on stage or in front of a camera reconstructing something of their lives, they have already gone trough a process of rehearsing, rewriting, and transforming the experience into a story. And for that, they have to take a distance from their own experience to become the storytellers and not the victims of their own fate. I think a good storyteller has to stay neutral to allow the audience to become emotional.

WNG

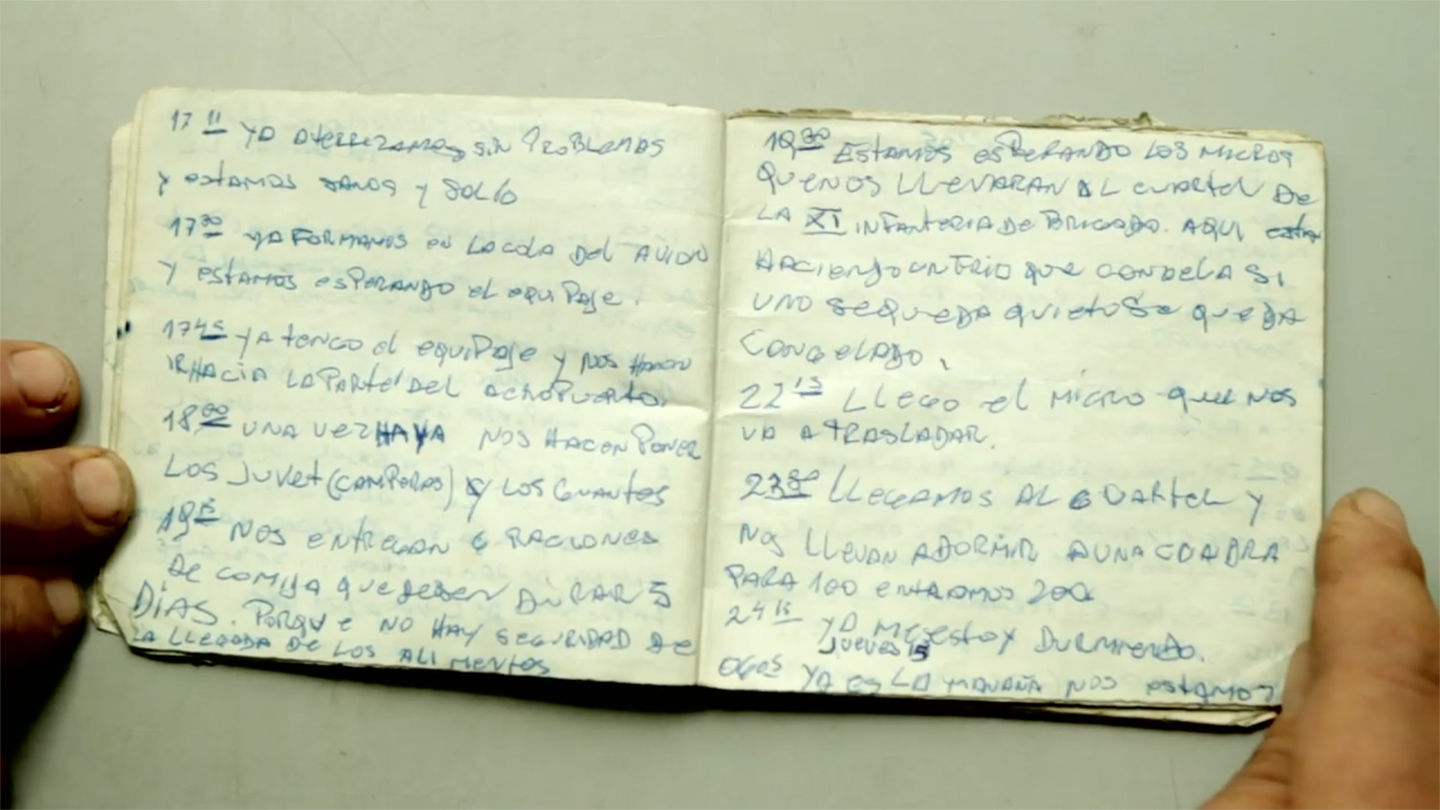

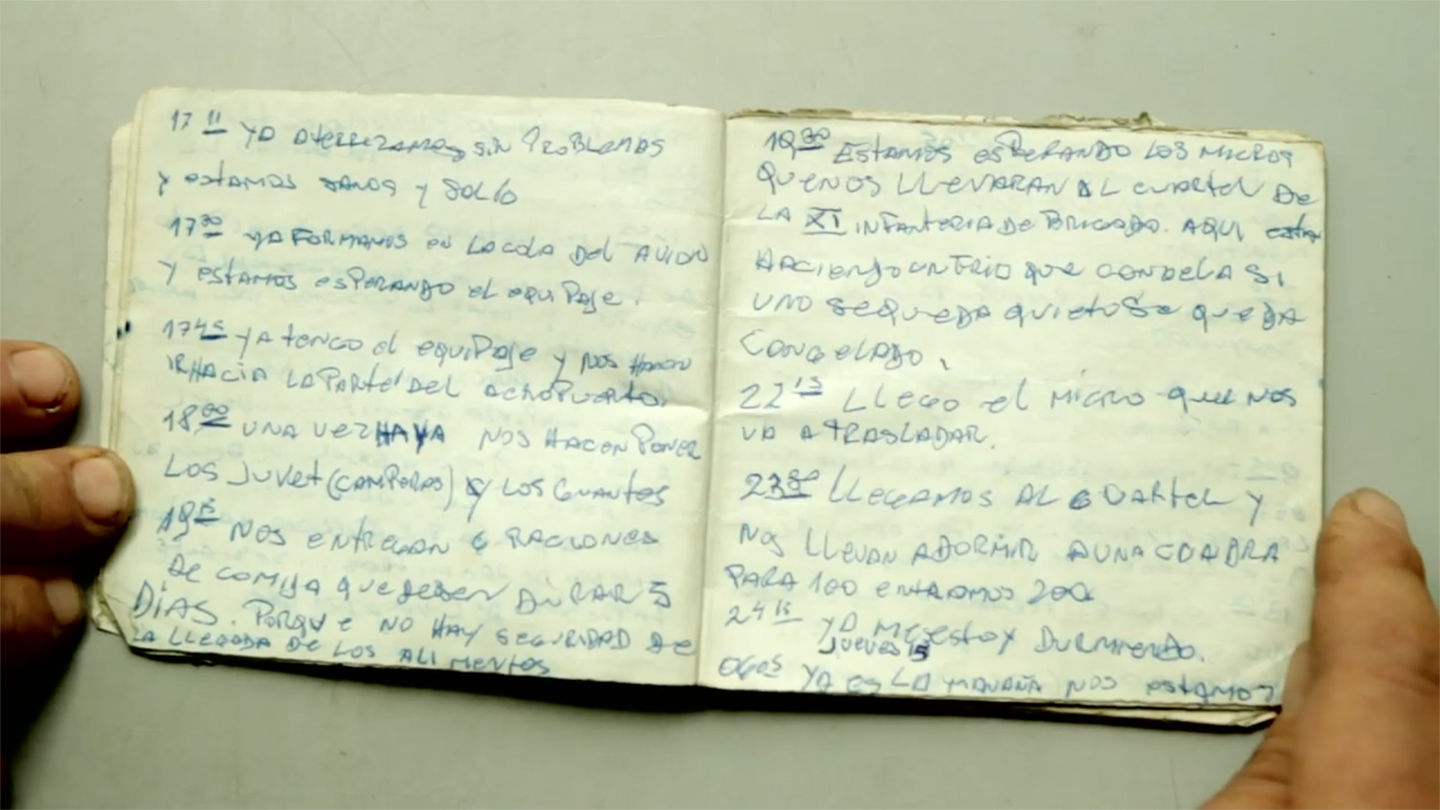

Can you speak about the relationship between personal memory and historical fact? Something that struck us was the factual nature of the diary piece beside the more personal selections of your other performers.

LA

I see the diary as a frame for all the other re-enactments. The diary of this soldier is a very detailed summary of facts: 13.45. I ate one plate of food, 15.02. We shot down a plane…. Everything is at the same level: the banal and the important. In this dairy there is no subjective narration, just facts ordered by time. But in the list of facts you can also see how a soldiers is trying to document every second of his time in the war, maybe to feel that he can control something or that he can put away the fear or maybe just to help him not to forget. All the unspoken experience of the war is in between the laconic lines of the diary.

When I asked the veteran to read it again he was shocked. He kept this diary for 35 years and he read it all in 40 minutes for the film. There are moments when you see in the tone of the voice how he has doubts whether to say something or not. The act of reading was his re-enactment, his way to go back in time.

And all the other re-enactments are one day in the big diary of the war that could be written by all those who went there. One single moment that stayed in their memory until the present. The other stories are a good contrast to the dairy. In each of the short videos we explore what war has done to these men.

WNG

You have such a unique way of storytelling across your practice, with both personal stories of your own and others. I wonder, who are some artists that have inspired you in working this way?

LA

So many artists. Do you want a list? Robert Smithson, Sophie Calle, Harum Farocki, Ana Cristina Cesar, Sei Shonagon, She She pop, Avi Mogravi, Silvia Plath, Rabih Mroué, Chantal Akerman, Federico León, Tim Etchells, Karl Ove Knausgard, Clarice Lispector, Rimini Protokoll, and so on and so on…

In conversation with Lise Haller Baggesen

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

How does your work respond to the pressures and politics that surround the female body?

Lise Haller Baggesen

Ideally, I would like to replace pressure with pleasure and politics with culture and take it from there. I believe the next feminist wave must be all about women’s right to pleasure — the pleasure we take in our bodies, our sexuality, motherhood, leisure, and professional and intellectual pursuit. I realize that is utopian, but I think this is a good starting point.

I sometimes wish the (art-)world was as interested in women’s CULTURE as they are in women’s BODIES. The female body appears so ubiquitously present in the cultural canon, but more often than not as a representation through the male gaze. By female culture, I refer to all places in which females assert themselves in a way that challenges that gaze. I am talking about the female voice, for example. How do we give the female voice a space to resonate, within our broader cultural field?

Frequently women are infantilized in the arts, by being seen and not heard. It is something that can happen when male critics (like Jerry Saltz or Dave Hickey — self declared feminist and ladies man, respectively) butt in and try to mansplain ourselves back to ourselves. Guys, I know you are only trying to help, but sometimes speaking from that kind of authority can come off as a tad paternalistic. Sometimes the most feminist thing a man can do is to shut up and listen!

That said, serious and mainstream art criticism is another field in which female artists are grossly underserved; what does it take for a female artist to get into Art Forum? (Does she have to wear a strap-on dildo, for example?) It happens, of course, but when you crunch the numbers the odds are not in our favor. Micol Hebron’s recent Gallery Tally project, makes it perfectly clear that — although we have come a long way since the Guerrilla Girls tallied up major institutions and coined the slogan “Does a Woman Have to be Naked to get into The Met?” — baby, baby, we are not there yet!

But back to your question: how does my own work respond to all this? I am somewhat weary of the female=body/male=head dichotomy, which is why I increasingly focus on the female voice within my work, through writing, audio, etc. My most recent project HATORADE RETROGRADE is my own personal “all woman show” — a femi-futurist adventure for which I commissioned an all female cast to write for a motley crew of female protagonists. I figured, since I had free hands with the show, the least I could do was to make sure it would pass the Bechdel test with flying colors!

WNG

Can you describe how you arrived at the idea of “Mothernism” and what it means to you?

LHB

Mothernism started out in the spring of 2013, as my Master’s thesis in Visual and Critical Studies from the SAIC. I had initially enrolled in the program as a mature student with the intention of shaking off that “mama-artist-syndrome” but found myself increasingly frustrated with the way my maternal experience was nixed when I brought it to the table — during discussions on feminist, gender and queer theory, for example. So I had to ask myself: “Am I the only person here, who finds this relevant?” before deciding “Hell no! If this is such a taboo, it must be because it touches a nerve. So, if nobody in this room wants to talk about it, I will write my thesis on it, and then we will talk about it.” That it has resonated with so many outside our classroom I had never dared to dream about — but I don’t mind at all!

The word “Mothernism” is an elision, associating both the good stuff — like mothering and modernism — but it also has some negative connotations, like sexism, ageism and abled-bodyism, which are often directed at the maternal body. This body freaks a lot of people out, to be frank, in myriad ways the stereotypical “female body” doesn’t. I mean; it probably has stretch marks, for starters. Scars. Not to mention an (oceanic and slippery) interior. So, it’s a little different.

WNG

In your work you address the “mother-shaped hole in contemporary art discourse” and in a portion of your audio from the Mothernism installation you note an experience of visiting a show at the Museum of Contemporary Art and asking yourself: “So, how does a MOTHER get bad enough to get inside the museum?”

Curiously enough, there seems to be an immense pressure on women in general to become mothers, yet there’s almost an air of criticism when women artists choose to become mothers, as if motherhood will take away their artistic ability. Can you elaborate on your personal insight into this conflicting issue?

LHB

I am really glad to hear you acknowledge this! It feeds into so much of what I am describing above, as the reason for me to write my thesis, and later my book, on the subject. Mothers in the art world are measured with an astounding double standard. Whenever you complain about the challenges you are facing, you are met with the counter argument that mainstream culture adores mothers and idolizes motherhood. First of all, that is not entirely accurate; consumer culture adores and idolizes every aspect of our lived experience that can be compartmentalized, consumed, and sold back to ourselves — but that of course is not the whole picture.

It is comparable to saying that mainstream culture adores Black culture, because it idolizes Black sports heroes and pop singers, and because everybody wears Nike sneakers. Or to tell queer and trans folk they are represented by, say, Caitlyn Jenner and television drama like “Transparent”. Then, imagine Black and queer artists being denied both authorship of their own experience and denied access to examining it in relation to the cultural canon, because, “everybody outside of the art world loves you, and in here we have different rules.” That happens to mothers all the time.

WNG

Have there been any significant artists who are also mothers that have inspired you along the way?

LHB

I am a painter, and as you can imagine the traditional painting canon does not include a lot of mothers (although some real motherfuckers)… so I spent my formative years as an artist as a “cultural necrophiliac” — meaning that I fell in love with a lot of dead guys. But I have no regrets — when you are in love, you’re in love — and I still adore the works of, say, Courbet, Manet, Munch, and Gauguin. People will tell you they were “just” a bunch of misogynists, Johns, and sex-tourists — which they factually were — but I hate that kind of essentialism. Spending time with the actual work (inside of the actual museum which is where you will find it) will reveal it to you in another complexity, giving you an event horizon that is longer than five minutes. One friend of mine once said to me “seeing is not believing, but it’s a practice,” and another (my yoga teacher) told me to “do your practice and all will be revealed.” I am of the conviction that you can learn a lot about yourself, from artists that have little in common with yourself — or maybe more than you think — and that all will be revealed if you practice returning that male gaze of the art historical canon, unflinchingly.

I was thinking about all this, as I was walking through Kerry James Marshall’s Mastry retrospective at the MCA; his is a brilliantly wrought argument for Black representation, and he always keeps his eyes on the prize — but the “female problem” cannot be solved through (visual) representation only, and if we think so we may be painting ourselves into a corner. There has always been plenty of female flesh on view in the museum, as we discussed earlier — hence the importance of making the female voice heard. These days, Jerry Saltz is hailing Kim Kardashian as the new Andy Warhol, but we cannot keep reinventing ourselves within the same critical paradigm — it’s a dead end. If visibility is power, why is Pamela Anderson not in office yet?

But back to your question: as part of researching “Mothernism” I have, off course, actively been looking to mother-artists for inspiration. Those mentioned in the book include Louise Bourgeois, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Cicciolina (who I consider a great performance artist). Perhaps not your typical mama-artists, but then again, the point of the book was to challenge this stereotype.

Last year (2015) I saw two extraordinary retrospectives of female artists, whose lives, in many ways, were defined by the maternal. Firstly, Paula Modersohn-Becker, who tragically died from an embolism shortly after giving birth to her first child (a daughter), explored the mother-child relationship in a series of intimate portraits and also painted the first naked (!) and pregnant self-portrait. (Something I was blissfully unaware of, when I did the same thing during my first pregnancy, almost 100 years later.) And secondly, Sonia Delaunay, whose baby blanket for her son was credited as her first abstract work of art.

I found it very inspiring how these two great artists clearly thought of themselves as “avant-garde” while totally redefining what that means (which I suppose is the very essence of being avant-garde?). Through these weighty exhibitions, they were being acknowledged as such — all the while critically (and playfully) positing the question to the viewer: “what happens to the avant-garde, when the mother laughs?”

This question (cleverly framed by Susan Suleiman) which was central to “Mothernism” is related to a broader one: “how do women think of themselves as avant-garde” — which in turn became the inquiry question for HATORADE RETROGRADE.

WNG

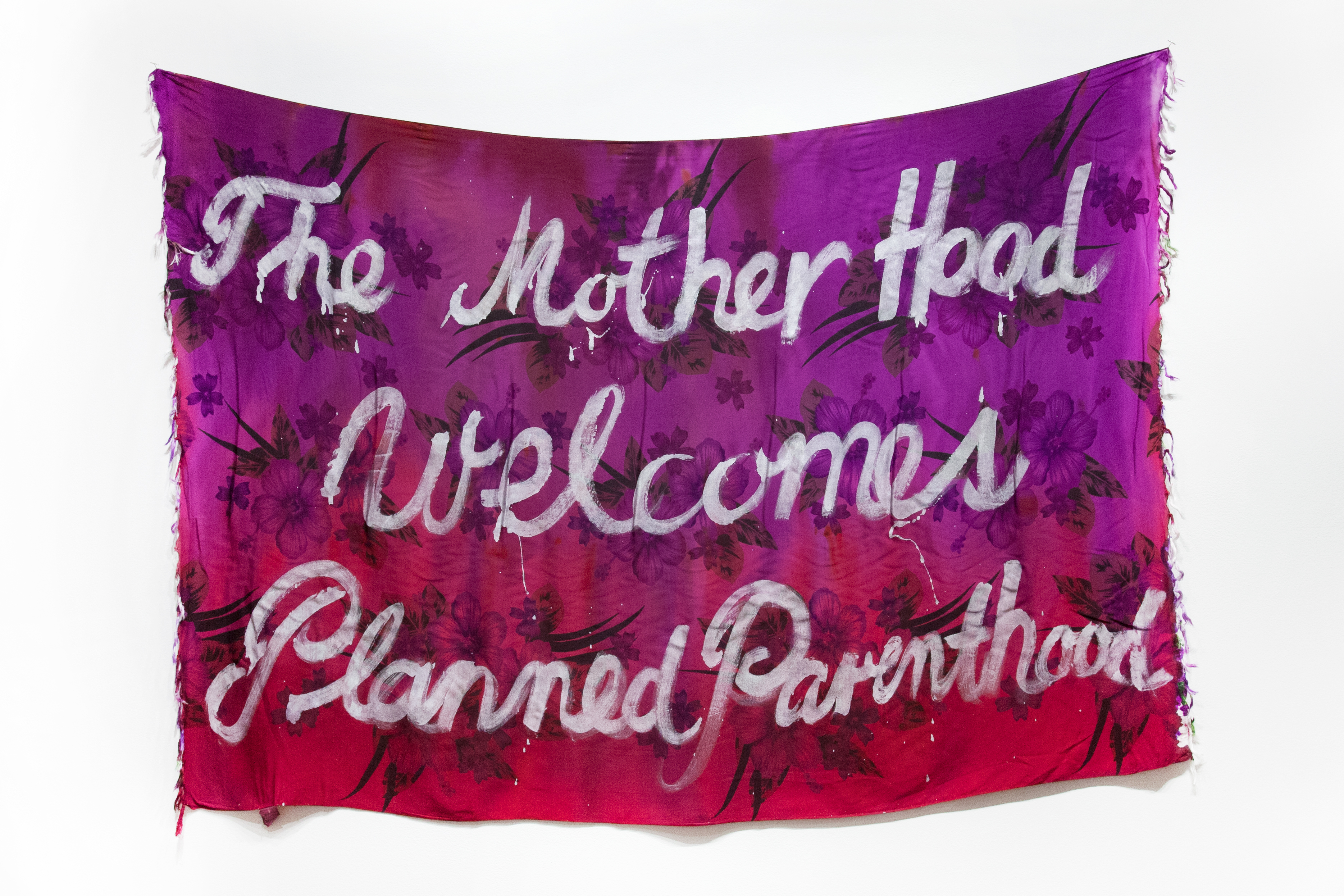

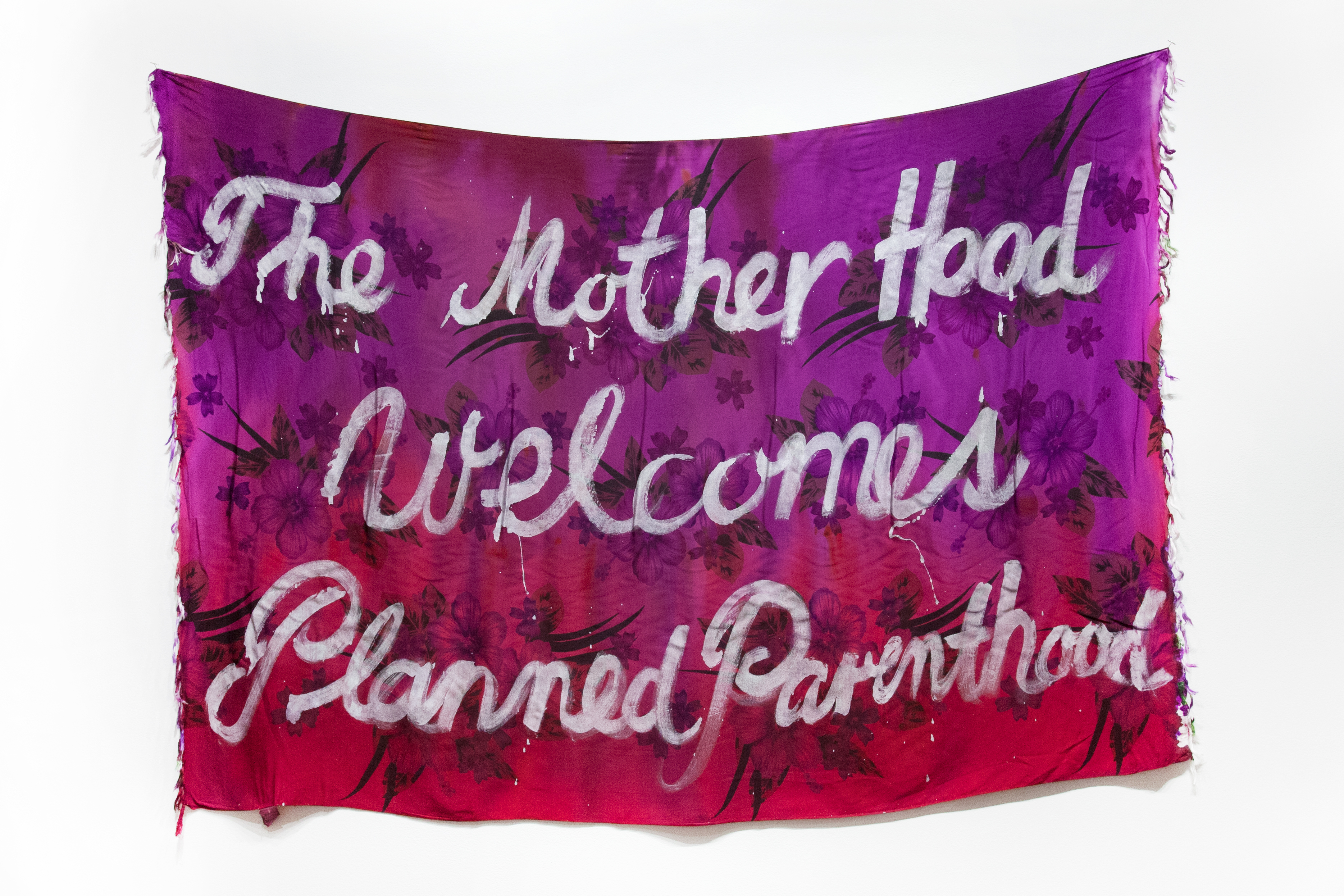

Your piece in Your body is a battleground is extracted from the immersive Mothernism installation. It reads: “The Motherhood Welcomes Planned Parenthood,” and I appreciate how loaded that phrase is. I would think some people might find motherhood and Planned Parenthood at odds with each other when there’s such strife between pro-choice vs. pro-life advocates. What does the sentiment of this phrase mean for you?

LHB

I made that banner last fall, when Planned Parenthood was under a lot of strain. Fraudulent videos were being released about their practices, and they were threatened with de-funding from the political side (we all know which side (!)). It just infuriated me how low some people will go, in order to defame this institution and the important work it does, including abortion.

The banner was included in my Hi(gh) Mothernism installation for the Elmhurst Art Museum Biennial, in the museum’s Mies van der Rohe house. In many ways, this iteration of the show was centered around the “suburban mom,” and I thought it would be fun to make a banner that looked like it could be announcing a street festival, bake sale, or homecoming, in the “Mother Hood” — but with a subversive swag. I was at first a little worried that it would be too strong for a suburban audience — but then realized that my worry was entirely based on my own presumptions about suburbia.

At its core, Mothernism is about female reproductive rights. But those rights do not begin and end with the decision to terminate your pregnancy in the first trimester. Female reproductive rights include sexual education (and not the “abstinence only” kind), access to birth control, access to healthcare for the mother and child, access to affordable daycare and schools etc. etc. Only if these factors are in place can a woman make a truly informed, and truly personal, choice to become a mother or not.

The so-called pro-lifers… don’t even get me started on those, so I won’t… but, I think the pro-choice camp could be ready for a little self-reflection, and within that, a reexamination of the advances of the feminist movement. The current wisdom is based on a second-wave dichotomy of “destiny” and “choice.” Lean-in-feminists will have us believe that individuals who have made the “private decision” to reproduce, are solely responsible for carrying out this decision — but this is a neo-liberal privatization ideology in extremus — whereas in fact we have a collectively shared responsibility toward the next generation.

The assumption that motherhood and Planned Parenthood are at odds with each other is widespread, while in reality mothers make up the majority of people seeking abortion services. (The numbers fluctuate, but an oft-quoted ratio is 60% mothers to 40% non-mothers). I guess that has a lot to with mothers knowing what they are getting into themselves, and also, with what kind of world they want to put kids into — and that is, perhaps, not one where women are reduced to mere breeders, or where they are forced to choose between motherhood and a career.

Lastly, there is a time to Mother, and there is a time not to. From my own experience I will posit that I was better equipped to take on motherhood at thirty, than I was at seventeen. That said, if we stopped slut-shaming teen moms — and instead became the global village it takes to raise the children of the world — maybe they would have a better shot at parenting, so I’m just putting that out there!

WNG

I’m interested in how in the audio/text piece of this project appears as a collection of letters all signed “Love, Mom” — a small but comforting phrase most of us have read time and again in our lives. What are your thoughts on the passing down of wisdom and experience between women, especially in the relationship between mother and daughter?

LHB

I walk my daughter to school every morning. I sometimes think I don’t have the time to do that, but I always feel like I don’t have the time not to do that. She doesn’t kiss and hug me goodbye in front of the other kids anymore, so I don’t know how long I will still get to do it — but on our way we sort out the world situation.

Mothernism is all about intergenerational feminism — as is HATORADE RETROGRADE, albeit with a very different flavor. Where Mothernism was a nurturing umami, hatorade has a more synthetic, bittersweet bite.

It all comes down to this collective memory, and how we pass it on: what do we savor and what do we chew up and spit out? Every single wave of feminism has a complicated relationship with the last one, and this current one seems to have a complicated relationship to itself — which makes it compelling, and self-reflective, but also somewhat navel-gazing. It’s a bit like grandmothers axe: if one generation replaces the head, another the shaft, is it still grandmothers axe? And should we use it to dismantle her house? Since we already have the right to vote, does that mean the suffragettes can teach us nothing?

This is why I favor the f-word, although many have suggested it is outdated, alt-modisch, a “kill-joy;” Feminism has a history we need to acknowledge, which is why we have to call it by its proper name — everything else is a euphemism.

In conversation with Iris Bernblum

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

The title of our current show, Your body is a battleground, is in reference to a well-known Barbara Kruger work. Feminist artists of the 60’s and 70’s, like Kruger, largely opened the doors for women to make the work we make today. Who would you say has been a strong female inspiration to you and your work?

Iris Bernblum

This kind of question has always been interesting to me, in the past I’ve always been hiding a kind of secret guilt about the fact that their have been very few women that have strong influences on my work. The strongest art influences on me for many reasons that I’ve only come to terms with recently have been primarily gay men… and a few straight ones. Namely, Felix Gonzalez Torres, Ugo Rondinone, Nayland Blake, and Paul McCarthy. I’ve been recognizing recently in the studio how much they’ve sunken into my language — as a woman — as an artist. Part of this, at least for me, seems to stem from the gender fluidity of their work, the woman is present in it I feel, I am in there. Not explicitly, but the ways in which identity, the psycho/sexual, vulnerability and personhood are performed in their work speaks to me. Of course there are women I greatly admire and have certainly been influential, Reineke Dijkstra, in the way she makes vulnerability powerful, Cindy Sherman, Carolee Schneemann, but there seems to be a space in the queer dialogue, the female dialogue that I feel is unaddressed and perhaps in some way I’m speaking to that.

WNG

Women are faced with unrelenting pressures about our bodies — how we should dress them, what we should do with them, whether or not we should be allowed to choose what happens to them, etc. How does your work respond to these pressures and politics that surround the female body?

IB

Much of my work speaks to anxiety and the release of tension, within the body, within the mind. I like to think I create a space that embraces the body, with all its beauty and disgust, I want to acknowledge it all, put it out there, like an invitation. I think vulnerability is political. We are not given permission to be so, especially not women, we are never allowed to let our guard down, not about our bodies, our sexuality, our existence in the world, I like to imagine I give that permission.

WNG

In our image-based culture, we often see anti-abortion protestors using very explicit and exploitative images to elicit reactions. How do you think visual art might be able to counter those images?

IB

That is an interesting question… the first thing that comes to mind is with beauty. That we are all human, that we all have our shame, our weaknesses, it seems to me that these people with their soap boxes, their ideas about what is ‘right and wrong’ are some of the most terrified people out there. I would love to think that visual art could speak to their hearts — make them vulnerable — throw them off track so perhaps they could see beyond the rhetoric they have fed themselves.

WNG

In your circus themed works, I find the relationship between pressure and performance really interesting, especially when comparing the role of the clown to the role of the woman. Can you expand on that a little?

IB

Yes I recently had a studio visit where I was complaining that so many people ask me to perform, expect it when they look at my work, and it’s always just made me feel guilty for not meeting their expectations. But this visitor put my mind at ease by telling me I am absolutely not a performer, I am that nervous space right before the performance! I am endlessly grateful to this person who saw straight into me. The clown for me represents so many things. It’s been used repeatedly by male artists to exemplify a kind of shame; I think of Bruce Nauman, Paul McCarthy. Clowns, within the framework of my special circus, speak to a kind performance anxiety, the beginning of a kind of transformation, something to assist in the release. A decidedly female release. A good one.

WNG

Your piece in Your body is a battle ground is a text piece written using clown make-up on a mirror and reads, “Put the words in my mouth” That’s a really impactful phrase, and I love the way it works with the topics addressed in the show. What was your goal with this piece in particular?

IB

This piece came from my intense desire to speak back. To subvert the seemingly submissive message this sentence contains. It’s a kind of dare. Too many people out there telling women what to do, how to think, how to be, and nothing is ever right. Try me…

In conversation with Mary Helena Clark

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

Your film The Plant is featured in The Way The Mystic Sees. This self described spy film creates an immersive environment for the onlooker. As there is a sense of embodying the movements of the camera by the individual, the work provokes ideas of being followed and intruded upon. What is the emotion you were trying to create by juxtaposing the sounds of the hustle and bustle of life with these specific, unidentified characters?

Mary Helena Clark

Foley — the post production art of manufacturing sound effects to sync with an image — and bad foley in particular, were influential to the film’s sound design. The film is about the slippery truth in observation, the overlay of fiction on the observed, and sound that doesn’t quite match with the image does a lot to raise questions of its veracity or authenticity, both tricky ideas. Sound/image relationships become a kind of perceptual test. What is sensed as unnatural? What falls apart or into place when we register the construction of an observation? A key sound in the film is the distortion from wind on the mic that adds to the chaos of the street scene, points to the recording devices, and, like cinema verite style camera work, adds to the documentary claim of the image. If you listen closely you’ll hear inhales between the final “gusts” of wind, a bit of a curtain reveal. When making The Plant, I was interested in tricks-of-the-trade dealt with as a conceptual strategy.

WNG

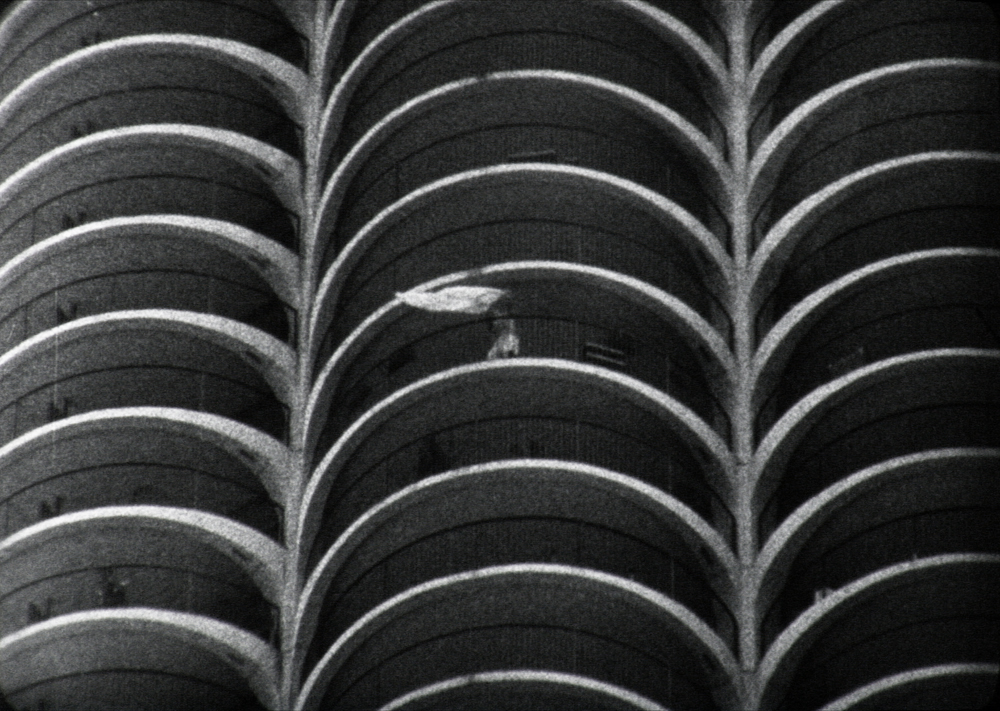

You are very intentional about the imagery you integrate into the work. The use of sequential images shot in ‘non-modern’ visuals places the viewer in a different environment and time, while simultaneously raising questions of who is being watched and followed today. Is this fluidity and interconnection of time integral to your piece?

MHC

All of the images were shot in 2011 and 2012 in Chicago on 16mm film. The format plus the telephoto zooms take the images out of the contemporary and allude to 70s films like Coppola’s The Conversation. I’m using the visual reference to access the tropes of the spy and thriller genres, more than to comment on temporality. I wanted to make a film that’s built around searching, inquisitive point-of-view shots. It is a question of who is being watched, but also one of complicity. Are those who appear in the film acting for the camera or are they unknowingly enlisted into it?

WNG

The Plant considers both sound and its absence, which creates moments of introspection for the viewer. Furthermore, the use of shadows and the walking stick act as metaphors for the physical presence of surveillance, which references cinema noir. Are you using these tropes to illustrate the more physical presence of surveillance as something more nefarious?

MHC

The physical presence that I was interested in was the body behind the camera, whose role shifts from observer when the film is capturing images on the street, to producer when the film’s images are directed and arranged. In a contemporary sense, I think of surveillance as totalizing capture, a large net of looking to be sifted later. The Plant uses a surveilling eye in a more subjective and conspiratorial way, asking how we make meaning. The line of what is or isn’t conspiratorial is both an abiding theme of the genre films The Plant references, and of the monomaniacal thinking artmaking requires. The problems of filmmaking are the problems of how you negotiate an abundance of things, constructing meaning in a way that threatens to impose the Paranoid’s (and also the Detective’s) rigorously ordered fantasy upon the orderless world.

WNG

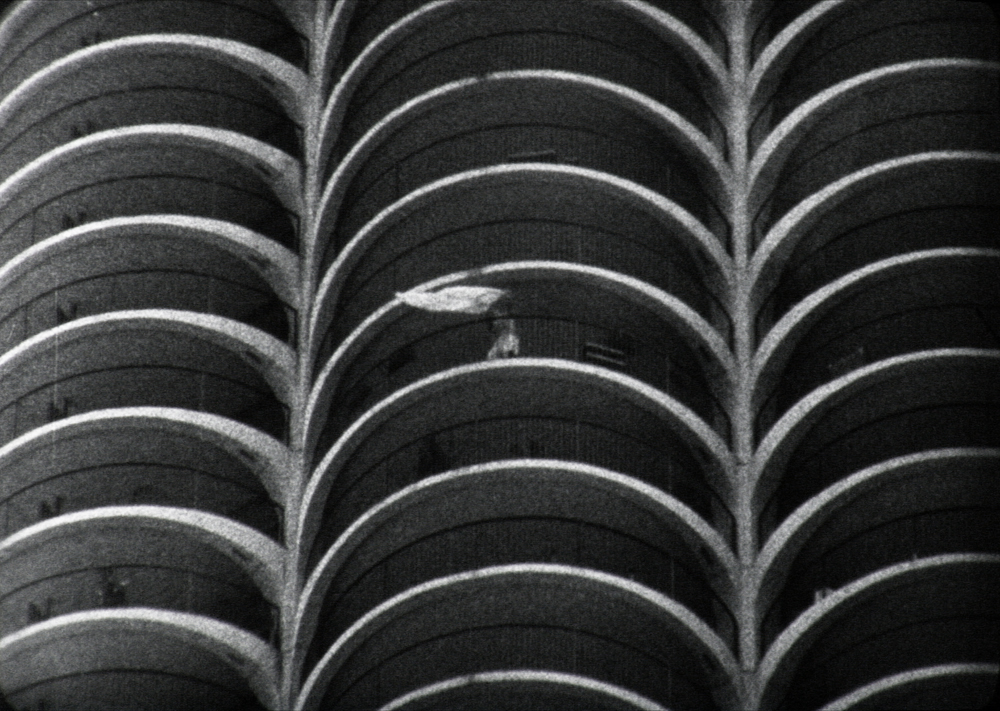

Often people create avatars as a way to mask their identities. However, there’s an anonymity about architecture which is also a tool for which to lose oneself or the other. Do you see the building as a symbol for concealment? And for who — the designer, the dweller, or the passerby?

MHC

The film was designed around the image of a tower, as fortress, panopticon, prison. I was interested in using the architecture of Marina City as a repetitive visual field that I could disrupt with the man waving from the balcony. I wanted the facelessness of the building interrupted by a single figure. It’s a blot, an ambiguous gesture that interrupts the image and begs for interpretation. We can wonder if the person is signaling us, or surrendering, or if we’ve “intercepted” a signal for someone else. The issue of being in or outside of a network of meaning is central to the film, and anonymity of those observed and of the person looking keeps the ricochet of signal and search going.

In conversation with Hope Esser

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

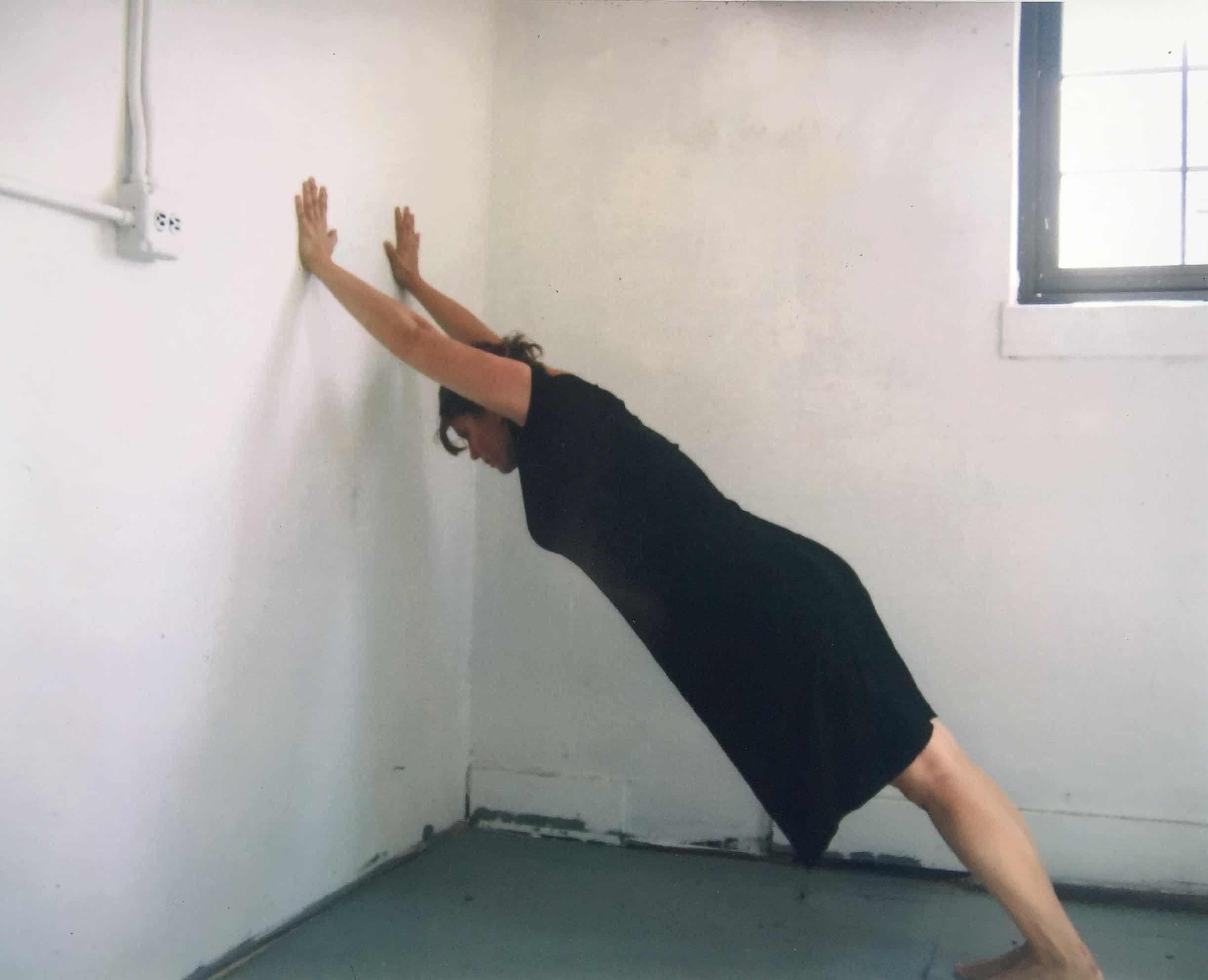

Your work spans across many disciplines, from sculptural to performative. Can you give us a brief introduction to your practice and your interests?

Hope Esser

My practice mainly concerns the body, and this is what my work comes back to regardless of medium. Before doing live performance, I started making videos in recording myself doing tasks. I also have had a lifelong interest in fashion/costume, and began making garments that did not make sense in a runway context. These pieces needed to be activated by a live body, which is how I came to performance. I still use all of these modes in my practice, and recently I have been making sculptural sets that can exist on their own, but also can become the stage for performance.

WNG

Who/what are your most prominent creative influences lately?

HE

My Students.

WNG

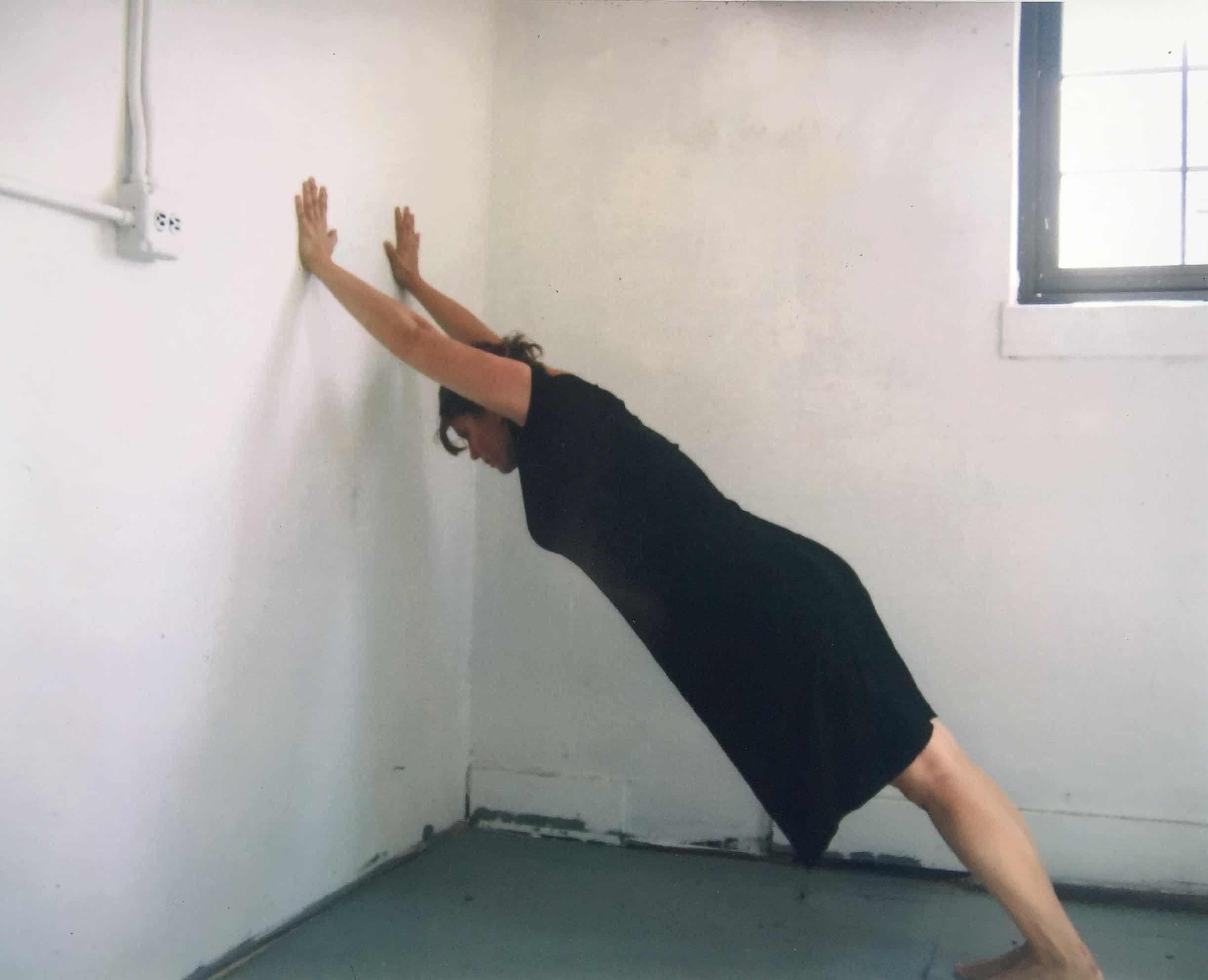

Your works in Your body is a battleground visualize the female form in unique and playful ways. How do you feel your work responds to the politics that surround the female body?

HE

When I made these pieces, I was thinking about the concept of “brokenness” and fragmentation and how objects can appear more perfect after they are broken, like an ancient ruin or sculpture. For the Torso piece I was thinking about the female body not as a languid nude but instead covered by a sweaty, discolored towel, maybe in a locker room. For the Crotches drawing, I was thinking about the female body and how she is historically portrayed as hairless, quite simply, I wanted return her hair to her.

WNG

I noticed in many of your performance works you’re engaging in acts of endurance, placing your body in strenuous and sometimes precarious situations. I’m particularly interested in the way these acts are explored in your pieces Contend, Soap & Anchor, and Don’t Worry, Baby because they seem to have a strong association to the role of being woman. Can you share more about your relationship with endurance?

HE

I am interested in examining what it means to be a “strong woman” both physically and mentally — so often my work draws from history and uses acts of endurance/power to explore femininity. Can femininity be presented in new ways, ways that encompass both physical and metaphysical strengths? In these works, I am often embodying a character who is resilient but at times also naïve or even pathetic in her endeavors.

WNG

Do you always perform before an audience, or are there times when the performance solely takes place before the camera? And do you prefer one over the other?

HE

Sometimes the piece takes place only in video form. I prefer the energy of the live event, but there are times when it is not possible to perform the piece live — where a specific location is important, for example, and there are times when the piece just makes more sense as a video instead of a live performance.

WNG

Your latest performance piece Of One’s Hour is complex in its multiple layers, and I’m sure the experience of it live is completely different from the video excerpt I watched on your website. I’m really interested in all of these soft and intimate kinds of gestures happening all around each other. Can you talk a little bit about this piece and the significance of the hour?

HE

Yes, the video excerpt is only two minutes long but the piece was an hour long — it is hard to encapsulate the whole work in a short excerpt. The hour became the structure for the piece broken up into six 10-minute sections. Each gesture was elongated into that 10 minute section, and I had an amplified kitchen timer that would go off every 10 minutes, abruptly breaking the atmosphere. The gestures derived from both personal experience as well as the reading I have been doing about proto-feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and her family, including her daughter Mary Shelley and her daughter’s husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley. I read and memorized Shelley’s poem Ozymandias in grade school, and also drew from this time period in my life for some of the other images. Through looking at these figures as well as personal history, the piece dealt with my ambivalence towards romance, and the inner battle that I fight between being a logical, independent, feminist and also being a highly romantic individual with big feelings.

In conversation with Max Guy

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

An extension of your previous work, you contributed a series of steel masks to The Way the Mystic Sees. How do you posit these—as disguises, or something more ceremonial?

Max Guy

This trio was described by a friend as a “punctuation” to my ongoing series of cut-out masks, which is currently a collection of around 100 or so iterations of masks that I started in 2017. Those were prototypes for a larger mask, cut from extruded Styrofoam, that I’d used in a performance. At that time I was interested in performing with the mask, so the material was more ergonomic, and the method of cutting out prototypes from paper was also a quick way to iterate. The decision to cut these from steel, and paint them in primary colors was also an ergonomic decision in a way. Steel is rigid so it can communicate a kind of flatness, and is magnetic, so it’s easy to hang. Primary colors came more intuitively as well in this case.

I don’t see them being used as a disguise at the moment, but I also wouldn’t completely abandon the idea. The three masks exhibited are more ornamental. If you can call the examination of the masks a ceremony, then they might be ceremonial masks. I’ve visited a lot of homes and tourist destinations where masks are treated as souvenirs, and divorced from any ceremony (other than their exchange). I grew up in New York City, in a home decorated with masks that were purchased as souvenirs and alienated from the traditions in Africa and the Caribbean that birthed them. Maybe for some people they hold a symbolic value as some sort of link to their past, but my fascination with masks came from the horror in gazing at these stoic, disembodied faces on the walls of my home. I saw them in my therapist’s office growing up and took comfort in the fact that if I couldn’t look him in the eye, I could look at them. For the moment, I’m happy to look as these masks formally, and to think about a face’s distinct social implications.

WNG

Cut forms feature heavily in your artistic practice. Is this a way to represent malleability of the art object, of that which it conceals, or which it may even project?

MG

I cut silhouetted forms, and my impulse to cut is a separate one from my use of outline or silhouette. Cutting-out a is a reductive action and I don’t know if looking at a silhouette is always reductive. As you said, we project/add quite a lot on/to a silhouette. I like the different things you can do with a cutout: you can circumscribe, circumnavigate, omit, divide, trace. Blades, lasers, water-jets, these are an entirely different set of technologies that are used to cut things from whatever happens with the use of silhouettes, outlines, stencils, etc.

For me, silhouettes imply shadows, concealment, projection, as you said. They evoke different cognitive and psychological principles. My favorite silhouettes are Kara Walker’s, because with them she’s able to make the viewer assume races, sexualities, racial hierarchies, inferred acts of violence, and all with one color.

Silhouettes and concealment are used in motion capture studies for CGI and surveillance — I don’t think that cutouts really have anything to do with this. I can build out from a silhouette, its flatness leaves a lot to be demanded, whole other dimensions. But when you cut something it’s already a three-dimensional material.

WNG

You frequently use color in your work, both semiotically as a way to impact the viewer. How does the use of, in this case primary colors, tie in with the notion of surveillance? As a method of distraction, or something much more engrossing?

MG

I don’t really have a color theory, and as I said before, the use of primary colors was more functional in this case. Red, blue and yellow are fundamentally unique from one another and my hope in usuing them was to distinguish each face, despite similarities in outline and cut forms. In this way, I was interested in creating characters out of each face. I like work that can use color evocatively in this way.

WNG

You’ve previously mentioned an interest in pareidolia, and how it’s used to build facial detection software. As our society becomes (amazingly even more) image-based, do you believe that the opposite can be taught — the face as an unrecognizable form as we become more detached from those around us?

MG

Facial recognition is a social thing — on a personal note I don’t know if I would want to learn how to un-recognize a face. The BBC series The Human Face, is a really fun show with John Cleese that goes into all of the reason humans need to be able to recognize a face and its myriad expressions. I read somewhere that 1 in 50 people live with Prosopagnosia, a disorder that leaves people unable to recognize faces. The painter Chuck Close has it, and probably also had a hand in how image-based our society now is.

One of the things I think about the most when making these masks is how in a number of years, I read more about artificial intelligence and machine learning than the mapping of the human mind, the kind of studies of empathy, and the functions of the brain. Even if this was dilettantish reading, the leap (and clear path) from cognitive science to machine learning has me very uneasy. Facial recognition technology — as an offshoot of artificial intelligence — is, to quote a friend, “a scientifically unsound cover story for expanding the surveillance state.” Out of paranoia I fear that even technologies used to un-recognize, to ignore, certain faces might be used in some sinister way. I hope that we’re not learning unlearning facial recognition!

In conversation with Meredith Haggerty

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

Can you tell us how you developed Tiny Retreat, an album of audio tracks specifically produced for Rebuilding the Present? How did the process evolve through the collaborations and conversations you had with many of the artists in the exhibition?

Meredith Haggerty

Holly Cahill, the exhibition's curator, expressed early on that she wanted the show itself to invite people to slow down and observe. I was inspired by affinities between her ideas and time I’ve spent in walking meditation with my husband. When we lived in Chicago, we’d go to a retreat center called Windhorse in rural Wisconsin for self-guided meditation retreats. The center is in a beautiful area with lots of rolling hills, and between sittings, we’d take turns leading each other on silent walks. At dinner one night, we talked about how being guided through the landscape was such a highlight for each of us. It gave us a chance to actively observe a space unfolding without fully navigating things. It felt like watching a film or listening to music.

I’d been playing with the idea of recording guided meditations for some time, and Rebuilding The Present seemed like the right space to begin that work. As I began to compose instructions, it became clear that I wanted these meditations to respond to the Weinberg/Newton Gallery space and the works in it. But since I now live in Chapel Hill, I needed to find a way to do it from afar.

I researched the space and the artists, but felt the need for even more connection. I asked Holly if she and I and perhaps some of the artists in the show could talk about our studio practices and the work going into the show. I am so grateful for their engagement because those conversations shaped tiny retreat. We talked about life experiences that informed our studio practices, ways in which audience interaction with our work is meaningful to us and things we would like to see happen with our work. It felt right to me that guided meditations that invite close engagement with the show were inspired by heartfelt, thoughtful conversation with artists in the show.

WNG

You received your MFA from the University of Chicago and later worked there in mind-body medicine teaching and implementing campus-wide curriculum and programing over a 10 year period. Can you share more about your experience as an artist working in mind-body medicine and how it may have informed the guided meditations in the exhibition? Where do these tracks veer from your experiences in the field of medicine?

MH

It is important to include that besides visual arts, I also have training in mind-body medicine including massage therapy, yoga, somatics and meditation. All of these combined allowed me to develop such a program.

The program at the University of Chicago began in Student Health. There, I worked alongside physicians and nurse practitioners to create complementary clinical care rooted in mind-body practices to help students manage stress and pain.

It was this work that led to yoga and meditation programs in campus chapels, galleries and conference rooms and then eventually to a curriculum at The Pritzker School of Medicine. I was constantly taking apart and reworking mind-body instructions and practice to fit into a variety of spaces and meet the needs of the particular group. It was lovely to work creatively with each space. The site-specific nature of that work kept me connected to my art practice even though there was this whole other career. It felt natural to continue working with those themes for Rebuilding the Present.

At University of Chicago I kept my work within the scope of the scientific literature on mind-body medicine. This happened naturally because I was reporting to physicians who understandably wanted this program based in science. It remains a great foundation for me. Rebuilding the Present was a permission to open things up and bring in themes as they were being explored by the artists with whom I spoke. Wander without moving and object holding pattern are meditations in tiny retreat that both incorporate moments of contemplation that, as far as I know, don’t have any literature suggesting they are tools for stress or pain management but are certainly rooted in awareness and agency and interwoven with instructions that do reflect the science of mind-body medicine.

WNG

It would be wonderful if you could walk us through one of the tracks you developed with an artist(s) in Rebuilding the Present and give us some insight into how their work influenced the recording? What do you hope that the visitors to the exhibition or the listeners on SoundCloud may take away from the album?

MH

First settle in is a track that was inspired by all of the artists with whom I spoke. The instructions begin with an invitation to find a comfortable place and position and then bring attention to other immediate surroundings by looking around. These instructions were drawn from our shared interest in installing work and inviting others to spend time with objects or ideas with which we have spent time, physically manipulated and developed a relationship with.

Then I invite observers to close their eyes and scan their body for sensations from breath, posture and tension. This part of the exercise is about noticing things that we typically take for granted or ignore, which is another theme that came up in each conversation. All of us were interested in the kind of intimacy that allows us to notice nuance. Whether it’s a slight variance in color or texture or a shift in the use or appearance of an image or object, each of us is curious about how layers unfold in our work and ways of inviting the audience to process this.

We then open our eyes and return to looking practice. The meditation closes with a tactile practice, similar to the beginning and my hope is that the track offers an opportunity to connect with the space in a way that consciously deepens over time and includes some stuff going on internally.

WNG

These works pair art and meditation to form the work itself. How do you negotiate the relationship between the two? Is meditation an important part of your practice?

MH

They certainly overlap, but they are quite different practices. A practice in studio art is, at the end of the day, at least partly about production and assessing what you make. Meditation practice, while not passive, often includes stepping back and noticing our urges to produce or judge situations then sitting with those qualities or exploring them within their larger context.

In this way, just like any life practice paired with contemplative work, meditation and art-making can inform each other. If I try to boil down my own experience, each practice contains the opportunity to notice my habits and avoidance strategies. From there, I can choose to work in a space closer to my heart and move into the other practice from that sweet and tender space. For me, the practices in tandem are like a friendship where both parties can totally be themselves and that honesty, with all the expressed messiness, vulnerability and weakness, strengthens the friendship and supports the individuals.

There are some intersections where I cannot distinguish the practices so well. Both seem to be sensory-based platforms that connect us to our immediate space including our internal landscape. Both practices require presence and a willingness to stay and return even when things are boring, fruitless or failed. Also, sometimes people think about starting an art practice or a meditation practice but don’t do it. I imagine we’ve all done this many times. We have an idea for a book or some paintings or we’ve read that meditation can help with a work or health-related goal but we let it sit there as an idea, something for the future. There can be lovely creativity in thinking about making art or meditating, but only if it leads us to starting where we are with whatever we have. Any practitioner of either form will tell you that some irreplaceable, juicy stuff happens only when you start practicing and you have to keep diving in.

Also, I don’t know if it works this way for others, but for me, metaphors, stories and images arrive more easily and take on more significance when I make space for and listen to the landscape beyond my own constant chatter.

In conversation with Cameron Harvey

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

Your Untitled, large-scale, airbrush paintings on voile are hung off the wall and in a staggered line that expands into the gallery as you approach the works. These double-sided paintings are positioned at enough of a distance from one another, so that visitors can walk and weave paths between each painting. Due to the lightweight, unstretched quality of the fabric, they undulate when air is displaced as you move past them. Can you tell us about how you chose the scale, installation, and configuration of these works as well as your intention to make them responsive to movement?

Cameron Harvey

I think of each painting as a figure painting that represents the possible energetic qualities of a person. I imagine the energetic body to be larger and more expansive than the physical body so, the paintings are taller and wider than the average person. I have been thinking about the interconnectedness of existence and how there are no solid forms, no boundaries between you and me, the chair and the wall, only atoms and molecules in constant motion and exchange with one another that make up what we, incorrectly, perceive to be solid, individual objects. Therefore, I wanted to make paintings that addressed ideas of visual perception and how what we see may not in fact be what is real, as well as ideas of motion, flow and interconnectedness.

I decided to install the paintings in a free-hanging way, as opposed to up against a wall like traditional works, so that they could be understood as both individual works and as parts of a whole, and so that the viewer could walk between the works to activate the installation and see both sides of the paintings. I chose not to anchor the bottoms of the fabric too tightly so that the paintings would move with the presence of the viewer. The idea of a diagonal line came about as it worked within the confines of the gallery space and allowed the paintings to peak-out behind one another so the imagery could overlap and the paintings could interact with one another in a visual way. It is intended that the viewer activate the paintings by looking at the imagery and attempting to perceive what marks are really there among the movement of the moire pattern, as well as allowing their own presence to be part of the visual and physical exchange, contributing both to the composition and to the movement of the installation.

WNG

Your interests span the cosmic and the cellular, our internal and external states, liberation and confinement, what is real and perceived, among others. The imagery in your paintings is not grounded in place, but rather depicts colorful, immersive, energetic fields in which interconnected complex forms emerge and dissolve. However, when you move closely to examine them, a moire pattern disrupts the surface of the painting, making the image difficult to discern. How do you think about and develop the activity within these paintings? What does the interference of the moire pattern symbolize for you?

CH

I think of the moire pattern as something that disrupts the marks and colors of the painting and which makes it difficult to understand where the marks reside, where they are coming from and how they are made. This is important to me because I am interested in creating a sort of ethereal mark that is not entirely there, or not fixed in space, to support my idea of creating bodiless forms and representing a sort of energy. The pattern also contributes a strong element of movement. Through the moire pattern, the paintings are in constant flux and therefore each person who views them has their own experience, and each experience is different depending on the light, the time of day, how many people are in the installation etc. It is important to me that the paintings interact with the viewer, that they do something, that they don’t just represent an idea, but somehow they are the idea. Through the movement, there is an element of impermanence, like the paintings can not be seen or captured, or made to be fixed or stil. Impermanence is one of the only guarantees in life, change is certain, nothing lasts forever and impermanence is about the fact that nothing is ever made up of the same particles, but that we are always in constant exchange with our environment. I like how the moire pattern creates an energy flow within the painting. To me both of these elements illustrate the nature of being on a molecular level but also on a philosophical one as well. The moire pattern is strongest where the colors are the most dense so I need to plan accordingly when creating the images.

WNG

What I See with My Eyes Closed represents a dramatic shift in scale, material and form from your hanging paintings in the gallery. In this small scale series on paper, you work to capture the fleeting afterimage we first see when closing our eyes. Each drawing is detailed, yet fuzzy, involving a labor intensive process in the depiction of a transitional moment. These drawings require tremendous memory and focus on a brief experience at the edge of vision. All of the drawings in this series are dated and you have compared these works to diary entries. Can you tell us about your process of making What I See with My Eyes Closed and what inspires you to capture these moments?

CH

The drawings are smaller and more portable than my paintings so I can work on them if I only have a few hours or if I am traveling, or want to be at home on the couch. They are also a collaboration with me and my physical environment where I don’t have to come up with the composition myself…but I can just close my eyes and try to remember the fleeting afterimage of the physical world and its light disappearing into a sort of vast inner space. Similar to my paintings they are made of layers of color and I think of them as representative of a certain place or time. I want to bring attention to moments of transition and attempt to capture the fleeting, which is impossible. I think of de Kooning and the ‘Slipping Glimpser’, he said, “You know, the real world, this so-called world, is just something you put up with like everybody else. I’m in my element when I’m a little bit out of this world: then I’m in the real world — I’m on the beam. Because when I’m falling, I’m doing alright. When I’m slipping, I say, ‘Hey, this is interesting.’ It’s when I’m standing upright that bothers me… As a matter of fact, I’m really slipping most of the time. I’m like a slipping glimpser.” I love that quote and how he addresses the journey of life and artmaking and how they are both slippery and it is hard to hold onto things to the point where letting go and being on the journey is the interesting part. I also feel like the act of making work for me helps me stay together while I am falling apart… and in some ways both my paintings and drawings are somehow disappearing or falling apart at the same time as they are coming together. It occurs to me that some people use the word transition to mean death, and I think, underneath it all, my work is about the relationship between the body and the Spirit and what happens when the objects on the physical plane disappear, about what is leftover. Fundamentally, my work is about death and what we are without the material world.

WNG

In addition to being an artist, you are also a yoga teacher. Yoga is described as a moving meditation. What drew you to learn and later teach yoga? What is your meditation routine and how does it inform your artmaking practice or vice versa?

CH

I began practicing yoga because I was making poor decisions and wanted to know myself better, it was really about dealing with stress and anxiety and low self-esteem. Yoga helped me so much that I knew I wanted to know more about it and share it with others so that is when I decided to do the teacher training and get out into the community. I am getting older and have been working in restaurants for 13 years so I practice asana in the morning to maintain some flexibility, and to be able to walk without limping, and turn my head when driving. I generally meditate while I am having coffee in the morning for 15 min or so, checking the internal weather to see what I am dealing with on any given day. I try to just sit and see what comes up and be without judgement, and as a perfectionist that is one of my biggest challenges, to accept myself as I am. Meditation helps me to see my emotions and thoughts, to acknowledge them, and let them go. Meditation is also about death, going into the deep self that is not physical, it is about impermanence and the idea that everything changes, as well as the fact that I create my own reality through my attitude, thoughts and perceptions. Ideas relating to trying to discern what is real, and exploring how my own perception shapes my personal reality, are important to me and what I explore in my artistic practice as well. Sometimes I can’t see the forest through the trees, and meditation is a way to pause and take stock, take the aerial view. I think of my painting installation at Weinberg/Newton in a similar way, when you are in it, you are caught up in the micro-focus of the moire pattern and a sort of minutia that is always changing. I have realized through this experience that the installation creates a bit of instability, or maybe even anxiety as a result. But you can really only see the installation as a whole, in a more calm and stable way, if you step back out of the installation, out of the woods as it were.

In conversation with Jaclyn Jacunski

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

You have two installations in Bold Disobedience, By Ways & Means and The Super Local. Can you speak on the issues that both works are addressing?

Jaclyn Jacunski

By Ways & Means is a system of pathways made of chain link fences. The fence is devoid of color, scaled down, and abstracted by a repeated pattern. It is a gritty and sobering architectural object surrounding private property, which becomes especially charged when taken out of context into the gallery space. The layout of pathways overlaps and shifts in scale, becoming visually complicated. The pathways and shapes are syncopated around the gallery in addition to a relief sculpture that is installed on a wall, appearing in struggle, pulling away as the chain link is bent and misshapen.

The project merges the atmosphere of the socioeconomic melting pot of Chicago. It is embedded with narratives of the city’s landscape, following a trip from home, through a neighborhood, to school. The work signifies systems that shape communities and lead the audience to consider issues of class and race, which lie beneath capitalist systems. The fence is an architectural object that folds in multiple meanings beyond gentrification. It also speaks to spatial justice, alluding to the prison industrial complex and restricted borders. The fences fashion a relational experience of walking through intimate experiences and spaces in Chicago.

The Super Local was created from west side neighborhood newspapers. The papers hang from library newspaper poles in vertical rows on the gallery’s wall. The top of the installation holds local papers then and gradates downward with paper designs I manipulate by blending and blurring images, which fade away. The papers give voice to the west side area’s lower-income residents, working as both formal and conceptual points of departure for the work. The papers recede into color fields, pulling from the newspaper’s color printing, ranging from a light tone to a dark shade while at the same time redacting and amplifying in intensity.

This installation responds to the sheer density of negative media coverage that creates a psychic mass, an overlay that can sometimes be very tense and aggressive. Citizens of lower income neighborhoods have to participate in these constructs everyday. The local community newspapers provide a counter point of view to the dominant narratives of how one sees Chicago’s west side. Mainstream media builds off of negative stereotypes, which often seem unreasonable to the lived neighborhood life. This local reporting communicates perspectives that are often overlooked — celebrating local achievements, talented people, creative events, strengths, and joys of community life.

WNG

Many of your works center around the urban landscape. What made you choose this subject matter, and how does it connect to the overall ideas of community and collective voice? The Super Local highlights local newspapers from specific Chicago neighborhoods that you have gradually blurred and degraded. It shows how, as a city, we often do not see these as growing, breathing neighborhoods, but instead are left with only a dying image. How do you think the youth community can help fix this? And through your artwork, how do you think you might be able to change it?

JJ

Every day, Chicago’s urban landscape is the space where I live and physically move through, and I use the experience as a type of research to interpret. It maps out forms and languages of our communal life that we build together. For me, the landscape and the built environment reveal poetic evidence that engages our senses and physical experiences in the world. This evidence helps me to gain understanding of our histories, psychologies, and relationships to power and institutions. I am inspired by the politics of space and the land as spatial justice. I look to it as a means of understanding power and how communities create their own narratives, finding spaces of freedom in the face of segregation and inequality.

I think activating spaces to take on meaningful issues and challenging dominant culture, as the Mikva Challenge curators have done at Weinberg/Newton Gallery, is one way to fix dying neighborhoods. Bold Disobedience shows the type of work that takes on reshaping our city and how people on the local level can essentially transform their neighborhoods and create a new construct within the urban environment. Things like engaging in community-building and cultural activities bring people together: organizing art events and music shows and open mics, making publications that take on issues to build understanding. There are super practical ways to heal our city by volunteering to rehab houses and bikes, help grow food, and mentor kids. In addition, it is important to be brave and speak out, analyze power, call representatives, and take action by organizing people to come together for change.

I hope in my work that I can connect with others in new, thoughtful ways, to build new connections and open up intelligent ways to move in the world. I see art as a kind of elixir or energy force that helps make change possible because it works through the senses and outside rigid systems.

WNG

How did you get interested in art? I wonder how you were able to combat the negative opinions associated with pursuing a career in art. I know many youths who would love to study art as a major, but outside factors often affect their decision.

JJ

I do not remember a time in my life when I was not interested in art and making things. Art has always had a place in my life. Looking back, I understand now it is not really a decision I chose but a vocation that is part of who I am. My practice really developed in high school, I worked a lot on drawing when my dad was struggling with an illness. I spent a lot of time at home working on art while spending time with him. When I went to college I began very practically on a pre-law track, and then took art and art history as electives — I loved the classes, then just never turned back and worked for my BFA.

It was hard for me growing up in a rural farming community where there was not access to the arts. The people in my life just did not understand that world or how to support me — it just did not make sense to them. They were so proud that I made it to college and were worried I was throwing away a huge opportunity to have a stable life. I will admit I did not always win against the negative opinions and gave up a few times but came back. When I was not working as an artist I was not in line with who I was. Yet, it was also hard to know where I belonged in the art world and to use my talents.

I think studying art is incredibly valuable and fulfilling. However, I encourage youth who want to take it on to work with mentors, and to build a supportive community. Art degrees are really what one makes of them. It can be easy to get by and not push the work. One needs to be self-driven, ambitious, have curiosity, and enjoy working independently.

WNG

What drives you as an artist? Are there any organizations you work with who are passionate about the same issues your work addresses?

JJ

I am in a constant search for understanding and constantly placing that search into form. I am driven to examine issues of inequality, power, and justice. Currently, I am working in North Lawndale to bring arts programming to the west side for the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. I love working on grassroots and community-level projects. I volunteer at West Town Bikes, support several women’s empowerment organizations, and am very involved in community art spaces like Spudnik Press.

WNG

What does “community” mean to you?

JJ

“We are tied together in the single garment of destiny, caught in an inescapable network of mutuality.” This is a quote by Martin Luther King, Jr. that influences my own views on community. I see community as a way of affirming that reality is made up of parts that form an interrelated whole; in other words, that humans are dependent upon each other. Community defines our relationships with one another and to the Earth. It is the courage to love and care for people as we love and care for our own families. It is a society based on justice, equal opportunity, and love.

WNG

In your work Start Together, which exhibited at the Chicago Artists Coalition in 2016, you talk about the fence as being an indicator between the rich and the poor throughout the city of Chicago. Can you expand on that?

JJ

I was thinking about value and how the city of Chicago cares for some communities differently than others communities. How does poverty happen and what systems sustain and support inequity? In Start Together, I created a labyrinth of orange plastic fencing, a material that litters empty west side lots. It seems to be draped everywhere. Though it is a material that one typically sees in other places as well, in Chicago it often lands in bulk on speculated land and outdoor spaces that are left behind and uncared for. Those who enter the labyrinth I created contend with the dizzying pattern and maneuver in a complicated space. The material holds clues about the way Chicago neighborhoods are valued along with how we feel valued in the city. It addresses complications of property in any neighborhood. It also highlights the underlying tensions from the changes or necessary changes not happening in a community.

WNG

Further, how does this observation make you feel about the future of Chicago, and even the U.S.?

JJ

I believe that together we must work for change, furiously.

In conversation with Anna Elise Johnson

Weinberg/Newton Gallery

In describing your work, you talk a lot about the power of images and their ability to reinforce social, political, and historical norms. Can you tell us about the specific kinds of imagery you use in your work and where you find it?

Anna Elise Johnson

I continuously collect images produced since the end of the Cold War that support the advanced-capitalist ideology we call neoliberalism. I look for photos that mark the historical shift towards the notions that freedom is best protected by free markets, and that government should be small and function only to guard market freedom and private property. I have gathered imagery from the last thirty years of political and economic negotiations, as well as from the protests and upheavals intended to counteract such negotiations. My sources for these images include the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, the International Monetary Fund and World Trade Organization photo archives, the State Department’s Flickr page, news sites from around the world, and Google image searches for specific negotiations and protests.

WNG

What comes to mind when you consider the image of power?

AEJ

I think of power in the Foucauldian sense that power is to be found everywhere. It operates from the top down as well as from the bottom up. I do not believe that there is a single image of power but rather that multiple images appear as nodes in the network of operations of power. Images are produced intentionally to support oppressive power structures, but because power is everywhere, images can also be used as emblems of resistance to challenge those structures.